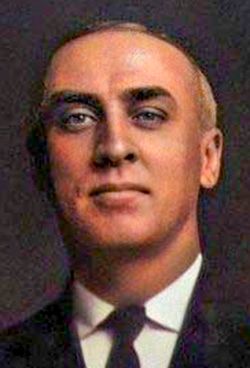

Though they were well paid compared to other steel mill jobs, puddlers were often maimed by lumps of molten iron hurled onto their legs and feet. They risked their life and health daily and often did not live past 50. David Jenkins was orphaned at 16 when both of his parents died within months of each other in 1884. Supporting himself through college, he attended Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, from 1887-1888 and 1889-1892, graduating with an M.E. (Master of Engineering) in Electrical Engineering in 1892. In 1892, he was a admitted to membership in Sigma Xi, the scientific honor society that was founded at Cornell in 1886 where members are invited to join based on peer-evaluated achievement

His first employment was in Steelton, Pa., as a mechanical engineer in the steel plant there. He was married on April 23, 1895 to Kate Hill. They had three children, Sarah Alice (1896-1937), John Hill (1898-1991) and Herbert Leslie (1899-1968).

With the outbreak of the Spanish American War in April, 1898, Mr. Jenkins, like other skilled engineers, volunteered to join the United States Navy, where he was commissioned as an Assistant Engineer, the equivalent rank of an ensign. He served from May 14, 1898 until October 29, 1898 and was assigned to the iron-hulled, twin-screw monitor, U.S.S. Amphitrite (BM-2). The ship was operating out of Key West, Florida on blockade duty, which expanded in late July to include the waters off Cape-Haïtien, Haiti. Amphitrite shifted her operations to Cape San Juan, Porto Rico, on August 2, 1898, where she remained offshore for two weeks.

During the night of August 7, 1898, a landing party of two boats with 35 of her crew engaged in the Battle of Fajardo and defended the Fajardo Lighthouse and approximately 60 refugees from the neighboring town against a superior Spanish assault force of between 150 and 200 men. Newly commissioned Assistant Engineer Jenkins, though with no prior military experience, was one of the four officers leading the engagement.

The Battle of Fajardo (Cape San Juan, Puerto Rico):

President McKinley and the War Department had ordered Army General Nelson A. Miles to land his troops at the western most point of the island, Cape San Juan and nearby city of Fajardo. However, as the planned-invasion neared, Miles unilaterally decided to land his troops at Guánica, on the southwest coast of Porto Rico, in part, because the American press had announced the planned invasion at Cape San Juan and the Spanish were expecting it. While this would give Miles some tactical advantage of surprise over the Spanish, it also conflicted with standing orders given by the naval commanders based on the previously desingated landing site at Cape San Juan.

Following orders from Admiral William Sampson, chief naval commander for operations in the West Indies, the monitor USS Puritan under Captain Frederic W. Rodgers proceeded to the anchorage off Cape San Juan, arriving on August 1. As Capt. Rodgers wrote in his report on August 2, "There are no signs of a rendezvous or landing here, although it appears to be a very good place for the purpose and vessels could coal without difficulty. We were joined here yesterday by the transports Mississippi and Arcadia. These vessels were ordered here to make a landing, but are at a loss what to do, as no information is available. I find no collier here, as was suggested in my orders, nor any instructions."

Making the best of the situation, Capt. Rodgers ordered an armed landing party of sailors and marines in two boats to make a reconnaissance. Once ashore, the sailors raised the American flag at the Fajardo Lighthouse and went to within a half mile of the town of Fajardo before returning to the ship. With the arrival the next day of three more ships, Amphitrite, USS Leyden, and the collier, USS Hannibal, the out-numbered 25-man Spanish garrison stationed in the city notified the Spanish command in San Juan, 60 miles west, and were told to withdraw.

Fearing an American invasion was imminent, the mayor of Fajardo, Dr. Veve Calzada, entreated the Spanish military commander in San Juan to send troops to defend his city. Mistakenly believing that the Spanish were not coming to fight the Americans, the intrepid mayor and town leaders then went to the Fajardo Lighthouse and secured an invitation to meet with the American naval commanders offshore to plead their case for the Americans to protect them from the Spanish.

Meeting on Amphitrite with Captains Rodgers and Charles J. Barclay of Amphitrite, the Fajardo mayor and several civic leaders convinced the two naval captains to protect the women and children of the more politically sensitive town families from Spanish reprisal. Unknown to the American commanders, the Spanish Governor General Macias was responding to the American presence and on August 4, ordered approximately 200 troops led by Colonel Pedro del Pino, to recapture Fajardo.

Early on the evening of August 6, with Amphitrite and the other American ships anchored about 1,800 yards offshore, Captain Barclay ordered a landing party of 14 petty officers and men armed with rifles, pistols and a 6mm Colt machine gun under Ensign K.M. Bennett, with Assistant Engineer Jenkins, Naval Cadets William H. Boardman, Paul Foley and Pay Clerk O.F. Cato to reoccupy the Cape San Juan Lighthouse. Almost immediately, a second boat of 14 armed petty officers and men under naval Lt. Charles N. Atwater with Assistant Surgeon A.H. Heppner was dispatched, with Atwater to take command of the landing parties.

Atwater ordered Bennett's men to proceed ahead to reoccupy the lighthouse and light the lamp, while his boat squad first secured both boats before following them up to the lighthouse. Given his engineering background, Mr. Jenkins was probably tasked with overseeing the lamp being relit.

Meanwhile, in Fajardo, when Spanish Col. Pino first led his troops into the city they found it mostly deserted; about 60 of the women and children of the cities prominent families that were deemed most at risk, had been authorized by Captain Barclay to be quartered in the lighthouse with the American petty officers and men, while some 700 Fajardans who could not be accommodated were camped out in the adjacent hills.

Though no attack materialized the first night, Ensign Boardman was mortally wounded after he initially entered the lighthouse with three men when his revolver dislodged from its faulty holster, fell to the marble floor and discharged striking Boardman in his left inner thigh. Assistant Surgeon Heppner initially believed it was a flesh-wound, although Boardman suffered a large loss of blood. He expired two days later on the Amphitrite, where he was evacuated that night when the ship's surgeon came to accompany Boardman and the assistant surgeon back to the ship. Cadet Boardman was one of only 23 combat-related navy deaths during the Spanish American War and the only death during Porto Rican operations.

The next day, August 7, the landing party engaged in arms practice and fortified the lighthouse for the expected assault by Spanish troops. Windows were blocked, sentries placed, and the Colt machine gun was mounted on the roof to "sweep the lane". On the 7th and 8th of August, native horse-men repeatedly galloped up to the navy men "with the wildest of rumors" estimating the Spanish were planning attacks with 500 men, a figure hyperbolically increased to 800.

On the 7th, Jenkins and Foley returned to Amphitrite and on the 8th, Jenkins returned to the lighthouse with Gunner Campbell and a relief party for half the men, who returned to ship, including Ensign Bennett and Pay Clerk Cato.

Just before 11 on the night of August 8, 1898, Lt. Atwater thought he saw moving figures in white, on the edge of the woods 250 yards from the lighthouse. At 1145, with moonlight breaking through the clouds, he saw several men in the brush on the edge of the woods. Without giving an alarm, he instructed the lookouts to be on heightened vigilance. As he was heading to the yard gate to order the corporal of the guard and sentry to come inside the light-house, those men came running up and announced they had seen Spanish troops in the road. Almost immediately, a volley of gunfire erupted from the surrounding woods.

Atwater ordered the lighthouse lamp doused as a signal to the three armed ships lying offshore that the light-house was under attack. The cruiser, USS Cincinnati, the only ship with an operable searchlight, trained it on the hill where the lighthouse sat in order to direct secondary battery gunfire from Cincinnati, Amphitrite and Leyden on the attacking Spanish troops.

At about 1230 am, an errant 6 pound naval shell crashed through the 2 foot thick walls of the parapet, "within touch of six men not one was hurt" when the shell failed to explode. Lt. Atwater immediately ordered the lighthouse lamp relit. At about the same time, gunfire from the Spanish troops ceased and Atwater gave the order to cease firing shortly thereafter. 1,100 shots were fired from the 22 rifles of the navy men in the lighthouse. Lt. Atwater estimated the Spanish force was probably 72 infantry, 24 cavalry, with 2 killed and three wounded, one of them a Spanish lieutenant. The Americans retained control of the lighthouse and suffered no casualties.

Early the next morning, Captain Barclay decided to withdraw the landing party and civilian refugees as the advantage of continuing to hold the lighthouse seemed slight. The marine guard from USS Cincinnati under the command of 1st Lt. John A. Lejeune and a like number of men from Amphitrite (30) landed and covered the withdrawal. The women and children refugees were soon on board the USS Leyden which transported them to Ponce, Porto Rico. While the Battle of Fajardo was the only instance in the Porto Rican theater of operations where American forces retreated from a position, it was not a defeat. President Mc Kinley mentioned the engagement in his State of the Union address.

As Lt. Atwater wrote in his after action report to Captain Barclay that was published in the 1898 Annual Report of the Navy Department, Appendix to the Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation:

"To conclude, I am convinced that we could have held the place against a first rush attack of any number of Spanish soldiers not exceeding 200.

The relief party landed the morning of the 9th and the women and children to the number of 60 were sent to the Leyden without accident. We closed the light-house, and by your orders left the flag flying.

Of the officers with me at the light-house at the time of the attack, Gunner Campbell displayed special zeal and efficiency. Assistant Engineer Jenkins went beyond the mere lines of his duty in acting, although without previous military training, with coolness and credit as junior officer of the guard. Ensign Bronson was unconcerned under fire. . . .

. . . I must state that without naming nearly all who were there I cannot do justice to their merits. I feel certain they would have died if need be in defense of the light- house and women and children it contained."

Amphitrite departed Cape San Juan on August 18 for Guánica, Porto Rico, where it arrived the next day. She remained there until the end of August, when she steamed to St. Nicholas Mole, Haiti. Proceeding then to Hampton Roads, she arrived there on September 20, 1898. Departing that port six days later on September 26, Amphitrite moved up to Boston, Massachusetts, where she remained from September 29 1898 to February 25, 1899.

Mr. Jenkins returned home to Steelton, Pennsylvania after his discharge from the navy on October 29, 1898. On July 28, 1899, his wife, Kate, tragically died at age 32, three weeks after the birth of their third child, leaving him with three small children to support. While Mr. Jenkins financially supported his children, they went to live with their maternal grandmother and two aunts who raised them, while their father continued his engineering work in different locations.

In 1919, Mr. Jenkins served at the Army Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.) University established by General John J. "Blackjack" Pershing at Beaune, Cote d'Or, France, as an instructor in mechanical engineering in the College of Engineering. For most of his life, he worked for the Semit-Solvay company, a branch of the National Aniline and Chemical Company, as a maintenance engineer and efficiency expert. His headquarters were in Syracuse, N.Y. He spent years at the plants at Detroit, Michigan; Syracuse, N.Y.; Marcus Hook, Pa., and Brooklyn, N.Y.

David Jenkins retired in 1921 and spent his remaining years with his family in Milton, Pennsylvania, where he farmed and was a respected citizen. He was a member of the Milton First Baptist Church, Corinthian Lodge No. 240, F. and A. M. of Detroit, Mich., a thirty-second degree Mason, a Shriner, and Rotarian. Besides his fraternal societies and church membership, he was a proponent for establishing the Milton Public Library and the Otzinachson Country club.

He passed away from cancer ten days before his 62nd birthday in the local hospital. At his funeral service, attended by many of his fellow citizens, tribute was paid by State Librarian Fred A. Godcharles, followed by prayer by Rev. John Lentz as the church members and guests stood.

Though they were well paid compared to other steel mill jobs, puddlers were often maimed by lumps of molten iron hurled onto their legs and feet. They risked their life and health daily and often did not live past 50. David Jenkins was orphaned at 16 when both of his parents died within months of each other in 1884. Supporting himself through college, he attended Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, from 1887-1888 and 1889-1892, graduating with an M.E. (Master of Engineering) in Electrical Engineering in 1892. In 1892, he was a admitted to membership in Sigma Xi, the scientific honor society that was founded at Cornell in 1886 where members are invited to join based on peer-evaluated achievement

His first employment was in Steelton, Pa., as a mechanical engineer in the steel plant there. He was married on April 23, 1895 to Kate Hill. They had three children, Sarah Alice (1896-1937), John Hill (1898-1991) and Herbert Leslie (1899-1968).

With the outbreak of the Spanish American War in April, 1898, Mr. Jenkins, like other skilled engineers, volunteered to join the United States Navy, where he was commissioned as an Assistant Engineer, the equivalent rank of an ensign. He served from May 14, 1898 until October 29, 1898 and was assigned to the iron-hulled, twin-screw monitor, U.S.S. Amphitrite (BM-2). The ship was operating out of Key West, Florida on blockade duty, which expanded in late July to include the waters off Cape-Haïtien, Haiti. Amphitrite shifted her operations to Cape San Juan, Porto Rico, on August 2, 1898, where she remained offshore for two weeks.

During the night of August 7, 1898, a landing party of two boats with 35 of her crew engaged in the Battle of Fajardo and defended the Fajardo Lighthouse and approximately 60 refugees from the neighboring town against a superior Spanish assault force of between 150 and 200 men. Newly commissioned Assistant Engineer Jenkins, though with no prior military experience, was one of the four officers leading the engagement.

The Battle of Fajardo (Cape San Juan, Puerto Rico):

President McKinley and the War Department had ordered Army General Nelson A. Miles to land his troops at the western most point of the island, Cape San Juan and nearby city of Fajardo. However, as the planned-invasion neared, Miles unilaterally decided to land his troops at Guánica, on the southwest coast of Porto Rico, in part, because the American press had announced the planned invasion at Cape San Juan and the Spanish were expecting it. While this would give Miles some tactical advantage of surprise over the Spanish, it also conflicted with standing orders given by the naval commanders based on the previously desingated landing site at Cape San Juan.

Following orders from Admiral William Sampson, chief naval commander for operations in the West Indies, the monitor USS Puritan under Captain Frederic W. Rodgers proceeded to the anchorage off Cape San Juan, arriving on August 1. As Capt. Rodgers wrote in his report on August 2, "There are no signs of a rendezvous or landing here, although it appears to be a very good place for the purpose and vessels could coal without difficulty. We were joined here yesterday by the transports Mississippi and Arcadia. These vessels were ordered here to make a landing, but are at a loss what to do, as no information is available. I find no collier here, as was suggested in my orders, nor any instructions."

Making the best of the situation, Capt. Rodgers ordered an armed landing party of sailors and marines in two boats to make a reconnaissance. Once ashore, the sailors raised the American flag at the Fajardo Lighthouse and went to within a half mile of the town of Fajardo before returning to the ship. With the arrival the next day of three more ships, Amphitrite, USS Leyden, and the collier, USS Hannibal, the out-numbered 25-man Spanish garrison stationed in the city notified the Spanish command in San Juan, 60 miles west, and were told to withdraw.

Fearing an American invasion was imminent, the mayor of Fajardo, Dr. Veve Calzada, entreated the Spanish military commander in San Juan to send troops to defend his city. Mistakenly believing that the Spanish were not coming to fight the Americans, the intrepid mayor and town leaders then went to the Fajardo Lighthouse and secured an invitation to meet with the American naval commanders offshore to plead their case for the Americans to protect them from the Spanish.

Meeting on Amphitrite with Captains Rodgers and Charles J. Barclay of Amphitrite, the Fajardo mayor and several civic leaders convinced the two naval captains to protect the women and children of the more politically sensitive town families from Spanish reprisal. Unknown to the American commanders, the Spanish Governor General Macias was responding to the American presence and on August 4, ordered approximately 200 troops led by Colonel Pedro del Pino, to recapture Fajardo.

Early on the evening of August 6, with Amphitrite and the other American ships anchored about 1,800 yards offshore, Captain Barclay ordered a landing party of 14 petty officers and men armed with rifles, pistols and a 6mm Colt machine gun under Ensign K.M. Bennett, with Assistant Engineer Jenkins, Naval Cadets William H. Boardman, Paul Foley and Pay Clerk O.F. Cato to reoccupy the Cape San Juan Lighthouse. Almost immediately, a second boat of 14 armed petty officers and men under naval Lt. Charles N. Atwater with Assistant Surgeon A.H. Heppner was dispatched, with Atwater to take command of the landing parties.

Atwater ordered Bennett's men to proceed ahead to reoccupy the lighthouse and light the lamp, while his boat squad first secured both boats before following them up to the lighthouse. Given his engineering background, Mr. Jenkins was probably tasked with overseeing the lamp being relit.

Meanwhile, in Fajardo, when Spanish Col. Pino first led his troops into the city they found it mostly deserted; about 60 of the women and children of the cities prominent families that were deemed most at risk, had been authorized by Captain Barclay to be quartered in the lighthouse with the American petty officers and men, while some 700 Fajardans who could not be accommodated were camped out in the adjacent hills.

Though no attack materialized the first night, Ensign Boardman was mortally wounded after he initially entered the lighthouse with three men when his revolver dislodged from its faulty holster, fell to the marble floor and discharged striking Boardman in his left inner thigh. Assistant Surgeon Heppner initially believed it was a flesh-wound, although Boardman suffered a large loss of blood. He expired two days later on the Amphitrite, where he was evacuated that night when the ship's surgeon came to accompany Boardman and the assistant surgeon back to the ship. Cadet Boardman was one of only 23 combat-related navy deaths during the Spanish American War and the only death during Porto Rican operations.

The next day, August 7, the landing party engaged in arms practice and fortified the lighthouse for the expected assault by Spanish troops. Windows were blocked, sentries placed, and the Colt machine gun was mounted on the roof to "sweep the lane". On the 7th and 8th of August, native horse-men repeatedly galloped up to the navy men "with the wildest of rumors" estimating the Spanish were planning attacks with 500 men, a figure hyperbolically increased to 800.

On the 7th, Jenkins and Foley returned to Amphitrite and on the 8th, Jenkins returned to the lighthouse with Gunner Campbell and a relief party for half the men, who returned to ship, including Ensign Bennett and Pay Clerk Cato.

Just before 11 on the night of August 8, 1898, Lt. Atwater thought he saw moving figures in white, on the edge of the woods 250 yards from the lighthouse. At 1145, with moonlight breaking through the clouds, he saw several men in the brush on the edge of the woods. Without giving an alarm, he instructed the lookouts to be on heightened vigilance. As he was heading to the yard gate to order the corporal of the guard and sentry to come inside the light-house, those men came running up and announced they had seen Spanish troops in the road. Almost immediately, a volley of gunfire erupted from the surrounding woods.

Atwater ordered the lighthouse lamp doused as a signal to the three armed ships lying offshore that the light-house was under attack. The cruiser, USS Cincinnati, the only ship with an operable searchlight, trained it on the hill where the lighthouse sat in order to direct secondary battery gunfire from Cincinnati, Amphitrite and Leyden on the attacking Spanish troops.

At about 1230 am, an errant 6 pound naval shell crashed through the 2 foot thick walls of the parapet, "within touch of six men not one was hurt" when the shell failed to explode. Lt. Atwater immediately ordered the lighthouse lamp relit. At about the same time, gunfire from the Spanish troops ceased and Atwater gave the order to cease firing shortly thereafter. 1,100 shots were fired from the 22 rifles of the navy men in the lighthouse. Lt. Atwater estimated the Spanish force was probably 72 infantry, 24 cavalry, with 2 killed and three wounded, one of them a Spanish lieutenant. The Americans retained control of the lighthouse and suffered no casualties.

Early the next morning, Captain Barclay decided to withdraw the landing party and civilian refugees as the advantage of continuing to hold the lighthouse seemed slight. The marine guard from USS Cincinnati under the command of 1st Lt. John A. Lejeune and a like number of men from Amphitrite (30) landed and covered the withdrawal. The women and children refugees were soon on board the USS Leyden which transported them to Ponce, Porto Rico. While the Battle of Fajardo was the only instance in the Porto Rican theater of operations where American forces retreated from a position, it was not a defeat. President Mc Kinley mentioned the engagement in his State of the Union address.

As Lt. Atwater wrote in his after action report to Captain Barclay that was published in the 1898 Annual Report of the Navy Department, Appendix to the Report of the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation:

"To conclude, I am convinced that we could have held the place against a first rush attack of any number of Spanish soldiers not exceeding 200.

The relief party landed the morning of the 9th and the women and children to the number of 60 were sent to the Leyden without accident. We closed the light-house, and by your orders left the flag flying.

Of the officers with me at the light-house at the time of the attack, Gunner Campbell displayed special zeal and efficiency. Assistant Engineer Jenkins went beyond the mere lines of his duty in acting, although without previous military training, with coolness and credit as junior officer of the guard. Ensign Bronson was unconcerned under fire. . . .

. . . I must state that without naming nearly all who were there I cannot do justice to their merits. I feel certain they would have died if need be in defense of the light- house and women and children it contained."

Amphitrite departed Cape San Juan on August 18 for Guánica, Porto Rico, where it arrived the next day. She remained there until the end of August, when she steamed to St. Nicholas Mole, Haiti. Proceeding then to Hampton Roads, she arrived there on September 20, 1898. Departing that port six days later on September 26, Amphitrite moved up to Boston, Massachusetts, where she remained from September 29 1898 to February 25, 1899.

Mr. Jenkins returned home to Steelton, Pennsylvania after his discharge from the navy on October 29, 1898. On July 28, 1899, his wife, Kate, tragically died at age 32, three weeks after the birth of their third child, leaving him with three small children to support. While Mr. Jenkins financially supported his children, they went to live with their maternal grandmother and two aunts who raised them, while their father continued his engineering work in different locations.

In 1919, Mr. Jenkins served at the Army Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.) University established by General John J. "Blackjack" Pershing at Beaune, Cote d'Or, France, as an instructor in mechanical engineering in the College of Engineering. For most of his life, he worked for the Semit-Solvay company, a branch of the National Aniline and Chemical Company, as a maintenance engineer and efficiency expert. His headquarters were in Syracuse, N.Y. He spent years at the plants at Detroit, Michigan; Syracuse, N.Y.; Marcus Hook, Pa., and Brooklyn, N.Y.

David Jenkins retired in 1921 and spent his remaining years with his family in Milton, Pennsylvania, where he farmed and was a respected citizen. He was a member of the Milton First Baptist Church, Corinthian Lodge No. 240, F. and A. M. of Detroit, Mich., a thirty-second degree Mason, a Shriner, and Rotarian. Besides his fraternal societies and church membership, he was a proponent for establishing the Milton Public Library and the Otzinachson Country club.

He passed away from cancer ten days before his 62nd birthday in the local hospital. At his funeral service, attended by many of his fellow citizens, tribute was paid by State Librarian Fred A. Godcharles, followed by prayer by Rev. John Lentz as the church members and guests stood.