-----------------------------------

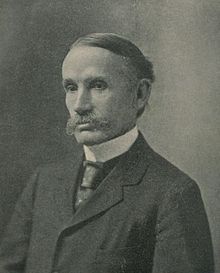

John Bates Clark (1847–1938) was the leading creative economic theorist active in America during the period when Alfred Marshall and the great Austrian marginalists were active abroad. He developed a distinctive form of marginal utility–marginal productivity theory, which he presented not as a completed system, but as a first approximation and an approach to further analysis. His major theoretical work was cast in the form of comparative statics: he constructed the model of an imaginary “static state”—one of complete competitive equilibrium—following which he analyzed the general effects of hypothetical dynamic changes, including the “dynamic friction” encountered by adjustments to these changes. His work is permeated by a social–ethical perspective that is not always well integrated with the technical economic analysis.

Clark was descended from New England Puritans. In him the original rigorous and doctrinaire features of this heritage had been relaxed and humanized, but a powerful religious and moral conviction remained. He was a lifelong active church member. His ancestors included farmers and prosperous traders; all were moved by public duty. His father was a modestly successful retailer in Providence, Rhode Island, who became a trusted adviser in the Corliss Engine Works, later moved to Minnesota in search of health, and there engaged in a small plow business.

Clark attended Amherst College, twice interrupting his study to take charge of his father’s firm when his father was incapacitated. After his father’s death he disposed of the plow business. He was graduated from Amherst in 1872, more mature and experienced than most college graduates.

He had contemplated entering the ministry but was advised to pursue economics by Professor Julius Seelye (later president of Amherst), who recognized Clark’s promise in that field. He studied in Europe for three years, mainly at Heidelberg and Zurich, his chief professor being Karl Knies. From his exposure to the German historical school he absorbed chiefly what fitted his predisposition toward a social–ethical perspective, which also made him sympathetic with British Christian socialism.

Returning to the United States, he married Myra Smith, also of New England ancestry, and joined the faculty of Carleton College, but for two years he was prevented from teaching by a crippling illness. Compelled to husband his limited working strength, he saved the best hour of each day for writing and began in 1877 to publish in The New Englander magazine the essays that later became The Philosophy of Wealth (1886). His most brilliant student was Thorstein Veblen, whose quality he appreciated and whose difficulties with the college authorities he attempted to alleviate. Veblen’s later writings had some kinship with the critical portions of Clark’s Philosophy of Wealth, with the difference that Clark’s criticism of social evils was always combined with a search for remedies.

In 1881 Clark went to Smith College, which was then six years old, where he taught until 1893, doing some part-time teaching at Amherst. He was active in forming the American Economic Association in 1885 and was its third president. During this time he formed a lifelong friendship with Franklin H. Giddings, then writing for a Springfield newspaper, and collaborated with him on economic writings. Having briefly presented his “social effective utility” theory of value in the Philosophy of Wealth, Clark staked out his marginal productivity theory of distribution in an early publication of the American Economic Association (1889). He presented his marginal productivity theory at the same session of the American Economic Association at which Stuart Wood presented his version. From 1893 to 1895 he taught full-time at Amherst; his students there included Calvin Coolidge, Lucius R. Eastman, Harlan F. Stone, and Dwight Morrow. Morrow spoke long afterward of the profound influence Clark had had upon him. Clark also lectured at Johns Hopkins, and in 1895 he joined the recently established faculty of political science at Columbia University. His more mature works appeared while he was at Columbia.

-----------------------------------

John Bates Clark (1847–1938) was the leading creative economic theorist active in America during the period when Alfred Marshall and the great Austrian marginalists were active abroad. He developed a distinctive form of marginal utility–marginal productivity theory, which he presented not as a completed system, but as a first approximation and an approach to further analysis. His major theoretical work was cast in the form of comparative statics: he constructed the model of an imaginary “static state”—one of complete competitive equilibrium—following which he analyzed the general effects of hypothetical dynamic changes, including the “dynamic friction” encountered by adjustments to these changes. His work is permeated by a social–ethical perspective that is not always well integrated with the technical economic analysis.

Clark was descended from New England Puritans. In him the original rigorous and doctrinaire features of this heritage had been relaxed and humanized, but a powerful religious and moral conviction remained. He was a lifelong active church member. His ancestors included farmers and prosperous traders; all were moved by public duty. His father was a modestly successful retailer in Providence, Rhode Island, who became a trusted adviser in the Corliss Engine Works, later moved to Minnesota in search of health, and there engaged in a small plow business.

Clark attended Amherst College, twice interrupting his study to take charge of his father’s firm when his father was incapacitated. After his father’s death he disposed of the plow business. He was graduated from Amherst in 1872, more mature and experienced than most college graduates.

He had contemplated entering the ministry but was advised to pursue economics by Professor Julius Seelye (later president of Amherst), who recognized Clark’s promise in that field. He studied in Europe for three years, mainly at Heidelberg and Zurich, his chief professor being Karl Knies. From his exposure to the German historical school he absorbed chiefly what fitted his predisposition toward a social–ethical perspective, which also made him sympathetic with British Christian socialism.

Returning to the United States, he married Myra Smith, also of New England ancestry, and joined the faculty of Carleton College, but for two years he was prevented from teaching by a crippling illness. Compelled to husband his limited working strength, he saved the best hour of each day for writing and began in 1877 to publish in The New Englander magazine the essays that later became The Philosophy of Wealth (1886). His most brilliant student was Thorstein Veblen, whose quality he appreciated and whose difficulties with the college authorities he attempted to alleviate. Veblen’s later writings had some kinship with the critical portions of Clark’s Philosophy of Wealth, with the difference that Clark’s criticism of social evils was always combined with a search for remedies.

In 1881 Clark went to Smith College, which was then six years old, where he taught until 1893, doing some part-time teaching at Amherst. He was active in forming the American Economic Association in 1885 and was its third president. During this time he formed a lifelong friendship with Franklin H. Giddings, then writing for a Springfield newspaper, and collaborated with him on economic writings. Having briefly presented his “social effective utility” theory of value in the Philosophy of Wealth, Clark staked out his marginal productivity theory of distribution in an early publication of the American Economic Association (1889). He presented his marginal productivity theory at the same session of the American Economic Association at which Stuart Wood presented his version. From 1893 to 1895 he taught full-time at Amherst; his students there included Calvin Coolidge, Lucius R. Eastman, Harlan F. Stone, and Dwight Morrow. Morrow spoke long afterward of the profound influence Clark had had upon him. Clark also lectured at Johns Hopkins, and in 1895 he joined the recently established faculty of political science at Columbia University. His more mature works appeared while he was at Columbia.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement