H. Dean Garrett

When the first pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, there were several blacks in the group. Later, pioneer blacks came as free people or in some instances as slaves of southern converts to the Latter-day Saint church. Together with others of African descent who came as workers on the railroad, these soon constituted a small black community in nineteenth-century Utah. One of them was Gobo Fango who left South Africa as a child and settled in the Salt Lake valley. He lived in the Tooele, Utah, area and eventually moved to near Oakley, Idaho, where he was killed in 1886. His life is a fascinating, yet sad story—and it remains controversial in Idaho and Utah today.

Edward Hunter, Presiding Bishop of the Latter-day Saints church, purchased a black slave named Gobo Fango sometime after 1865. Fango was fond of his employer, who helped the former slave become an independent sheepherder, and he included the bishop in his will. Fango was murdered by a neighbor in 1886 in a dispute over range rights. Engraving by H. B. Hall and Sons, New York, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved

Gobo Fango was born in the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa about 1855. He was a member of a tribe ruled by Chief Creile. His early life was shaped by the events of the Kaffir wars that raged around him. As a result of the wars and a concurrent famine, his young mother left her tribal home with her three-year-old son and a baby daughter and fled to a nearby farm owned by Henry Talbot.1 Her weakened condition made it impossible for her to complete the journey with both children, so she kept the baby with her and left Gobo in the crotch of a tree out of the reach of wild animals.2 After she arrived at the farm, Henry's boys rescued Gobo. He would soon become an indentured member of the family.3

The Talbots' lives changed dramatically when a friend introduced Henry to the Mormon religion. On December 28, 1857, he was baptized into the church. Six months later his wife Ruth and their children were also baptized; however, no records indicate that Gobo was ever baptized a Mormon. Soon, upon the encouragement of church leaders, the Talbots sold their farm and moved to Port Elizabeth to await the opportunity of traveling to Zion in America. That opportunity came on February 20, 1861, when they boarded the ship Race Horse and set sail for Boston. They had intended to leave Gobo behind with friends, but he complained so much they allowed him to accompany them. The family at that time consisted of Henry and Ruth, their fourteen unmarried children, and their married son Henry James Talbot and his wife and child.4 One account indicates that Gobo was hidden in a blanket and remained undetected until they were at sea.5

Except for a heavy gale in the Caribbean and a collision with another vessel in Boston harbor in which the Race Horse lost its bow, the trip was uneventful. However, the Talbots' arrival in Boston came at an exciting moment in history, for five days earlier shots had been fired at Fort Sumter and the Civil War had begun. President Abraham Lincoln had issued a call for volunteers, and many men were enlisting in the army. Flags were flying, martial music was playing, and great excitement was felt everywhere.

In Boston the Talbot family and Gobo boarded a train, traveling through New York and then on to Chicago. They met their first challenge to Gobo's presence in Chicago where certain people, undoubtedly influenced by the excitement of the war, accused the Talbots of owning a slave. Apparently they set about to give Gobo his freedom. According to one account Gobo, greatly frightened by the uproar, "fled inside the train and one of the ladies of the company hid him beneath her crinolines while the angry emancipationist searched the train without success. To avoid a recurrence of the trouble, Gobo was dressed in girl's clothing and his head was covered with a huge sun bonnet. At awkward times a veil was added to make sure his black face was completely hidden."6 The railroad ended at Joseph, Iowa. The immigrants then traveled to Florence, Nebraska, where they outfitted wagons and undertook their journey west to the Salt Lake valley, joining the company led by Homer Duncan. They arrived in Salt Lake in the fall of 1861 and wintered there. The following spring they moved to Kaysville, Utah, about twenty miles north of Salt Lake, and settled on a farm. Gobo remained with the Talbots and worked on their farm as an indentured slave.

Slavery was at this time still practiced by some Mormons from the south. In 1860 there were twenty-nine reported slaves in Utah.7 There was also a group of free blacks who had joined the Mormon church or who had settled in Utah for employment purposes. Between 1860 and 1870, the black population of Utah grew from 59 to 113. Some of this increase was due to the arrival of the transcontinental railroad.

Gobo was expected to work for the Talbots as a laborer and sheepherder, and life was apparently hard for him. He lived in a shed in back of the Talbots' house. One cold winter his feet froze, and he lost part of the heel on one foot. An acquaintance reported: "When he [Gobo] came to our place, his feet were badly frozen, and he was a cripple until his death. My first recollection was always seeing him wrapping his feet with cloths, and later I remember he had boots."8 She also remembered seeing Gobo take off his boot to show her brother his foot: "The heel was all gone, and he had wool in his boot so his foot would fit better."9 Gobo remained with the Talbot family until he was in his teens.10 Eventually the Talbots either gave or sold Gobo to the Lewis Whitesides family in Kaysville.11

A daughter, Ruth Whitesides Hunter, had a herd of sheep in Grantsville, Utah, and she was finding that her daughters were spending all of their time with the sheep and not learning the domestic sciences. When she remembered that Gobo was with her family in Kaysville, she asked her husband, Edward Hunter,12 if he would obtain Gobo for her. According to Hunter's biographer, "Edward paid for Gobo, then immediately put him on the payroll, just as he did all the hired hands. Gobo regarded Edward as his benefactor and was very fond of him. ..."13

The legal sanction for slavery in Utah ended in the spring of 1862. President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Some slave owners waited to release their slaves until 1865 when involuntary servitude was abolished throughout the United States.14 For instance, it appears that Gobo was sold to the Hunters after 1865.15

The Hunters took Gobo to Grantsville where he helped herd sheep in Utah's western desert through the 1870s. During this time he was able to develop a sheep herd of his own.

A group of Mormon settlers moved from Tooele and Grantsville to Goose Creek Valley, Idaho, as early as 188016 and began to irrigate and farm the land there and to raise sheep. About that same time, Gobo, two of the Hunter brothers, and Walter Matthews went to Goose Creek to run their sheep on the desert. Gobo and Matthews also leased a band of sheep from Thomas Poulton and his sons.17

At that time Cassia County, Idaho, which included Goose Creek, was a "huge expanse of lush range lands and high mountains."18 This area had already attracted the attention of cattlemen from the midwest and Texas who had moved into the area with large herds. The first arrived in 1871, and when sheepmen began moving into the same area, tension between the cattlemen and sheepmen arose. One report complained that "the sheep are getting so thick that they are eating the range out."19 This problem was compounded by the drought that began in the summer of 1885 and continued for several years. "It was dry and hot," a local history states. "Snow did not pile up in the mountains. The grass turned brown, and the cattle and horses cropped it to the ground."20 Due to the combination of overstocking and drought, the range was over-grazed. The cattlemen claimed first rights, the sheepmen disagreed, and a range war developed. Under pressure from the powerful cattlemen, Idaho's territorial legislature passed an act known as the Two-mile Limit which prohibited "sheep grazing within two miles of any possessory claim."21 The range rivalry continued to grow and the cattlemen issued their own edict that all sheepmen must leave.

In this setting early in the winter of 1886, Gobo Fango was herding his sheep in the Goose Creek valley beyond the cattlemen's deadline for leaving. Apparently he was close to the two-mile limit of a claim of Frank Bedke. Early one day Bedke and a companion rode into Gobo's camp and told him to leave immediately. The Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman reported that Gobo challenged Bedke to produce evidence of ownership of the land on which he was herding. Bedke indicated that he did not want to have trouble but wanted rather to be a friend. He dismounted his horse, caught Gobo off guard, and commenced shooting.22 The Deseret News account of the incident indicated that Bedke fired the first shot which "must have been aimed at his temple and carried away his eyebrow." The report continued that Gobo was beaten about the head with the pistol and was then shot again, "the bullet entering at the back part of the head and ranging to the neck, where it stopped close to the jugular vein and not very deep from the skin." A third time Bedke fired, "the bullet entering Gobo's side from the back and coming out near the navel."23 The newspaper indicated that Gobo recovered consciousness and overheard a conversation concerning disposition of Gobo's gun which Bedke had taken. Gobo was eventually able to "crawl about four and a half miles to the Walter Matthews home east of Oakley, holding his intestines with one hand."24 A doctor from Albion was summoned to take care of him, but Gobo survived only four or five days, during which time he made out a will providing for amounts of money to be given to acquaintances and friends, especially to the Hunter family. The rest was bequeathed to the Salt Lake temple fund and the Grantsville City "needy, poor people." Mrs. Solomon E. Hale indicated that "he left me $125 in his will before he died, as also some of my other sisters. He left $50 to one of them. ..."25

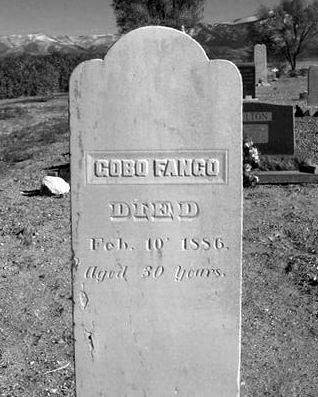

Gobo was buried in the Oakley, Idaho, cemetery. Marking his final resting place is a headstone with the simple inscription:

Gobo Fango

died February 10, 1886

30 years old

Frank Bedke and his companion rode to Albion, Idaho, where Bedke reported the shooting to the sheriff. A trial was held, and Bedke pleaded "not guilty due to self-defense." His companion backed his story, and the first trial ended in a hung jury. Bedke was brought to trial again one year later. This time the jury's decision was "not guilty." The events of that trial were reported in the newspaper:

"Frank Bedke, who was tried at Albion a year ago on a charge of killing Gobo Fango, colored, the trial resulting in a 'hung' jury, eleven voting for a conviction and one for an acquittal, has again been tried and acquitted, the first ballot of the jury showing 10 for an acquittal and 2 for conviction. Three ballots only were taken before an agreement to acquit was reached. The dying declaration of Fango was the most serious testimony offered. Judge Waters of Bellerue, Charles Cobb of Albion, and Ransford Smith of Ogden, defended Bedke."26

The man who killed Gobo Fango had traveled the world over as a seaman and then settled in Goose Creek Basin to raise cattle. Frank Carl Bedke was born in Rieth, Prussia, Germany, on November 22, 1844. He had limited schooling in Germany, and at the age of sixteen became a sailor on a ship bound for New York. He did not return to Germany, deciding instead to remain in the States. A family history states, "Near the end of the Civil War Frank Carl boarded a ship in Boston Harbor for San Francisco, sailing around Cape Horn."27 He spent about a year sailing the west coast and then worked on mining claims. In 1868 he traveled to Montana on a prospecting tour and wintered in Bozeman. In 1870 he went to Cottonwood, Utah, and joined the gold hunt, remaining there until 1877. After a short stay in Nevada, he moved to Park City, Utah, and sold milk to the miners. Then in 1878 he traveled to Grouse Creek, Utah, to winter 97 head of cattle. In the spring he took the cattle to Goose Creek Basin, Idaho, to a place now called Bedke Spring. He lived in a dugout and rode range for other operations until he was able to fully establish his own.

When he arrived in the Oakley area, it was about the same time the Mormons from Grantsville, Utah, appeared there. A close-knit group, the Mormons were not particularly open to outsiders. Bedke felt that he was an outsider, but he was intent on staying in the area. When an Indian uprising occurred, he remained and co-existed with the Indians while most of the other settlers fled to Kenton, Utah, for safety.

He married Polly Ann McIntosh on January 2, 1882.28 Polly Ann was born in Grantsville, Utah, in March 1863 to Solomon P. and Mary Harper McIntosh. At the age of seventeen, she drove a team and wagon from Grantsville to Idaho. Her marriage to Bedke was not viewed favorably by her family or the Mormon church, and this eventually led to her estrangement from both.

During the early years of their marriage, the Bedkes and their Mormon neighbors found themselves in conflict. One cause was the fact that Polly's husband was not Mormon. A second was the strong anti-Mormon feeling among other settlers in southern Idaho at that time. A third and perhaps more important source of conflict between the Bedkes and their neighbors was the dispute between the cattlemen and the sheepmen. The natural animosity between these two groups was amplified during the drought.

Despite these early difficulties, following his acquittal in the second jury trial Bedke became a successful and respected member of his community. One biographical volume stated that he was "active and forceful in the affairs of the community and aided in promoting its welfare both as a private citizen and as a useful public official, serving faithfully as a school trustee for nine years [and was] a firm and zealous working Democrat in political faith, giving loyal and serviceable support to the candidates and policies of his party."29 During the latter part of his life, he was described as a man "well prepared to meet all emergencies and perform every duty of citizenship with readiness and ability. He [was] a valuable element in the progress and development of Cassia County, giving substantial and helpful aid to every commendable undertaking for its improvement and the comfort and convenience of its people. Among the enterprising and public-spirited citizens of the county, he is in the front rank, and is secure in the esteem of all classes of the people."30

The death of Gobo Fango has inspired a voluminous amount of folklore and conflicting stories. The nature of the homicide is disputed by the descendants of Frank Bedke who feel that their grandfather was justified in killing Gobo Fango. This is based on several factors. They view Frank as an independent, self-sufficient man who reacted to any challenge to his rights or livelihood. In the eyes of his family, his reaction to the sheepmen, and especially Gobo, was right and justified because, according to their claims, Gobo was within the two-mile limit and refused to respect the lawful owner of the land. Second, the Bedke family finds it hard to believe that Gobo, so severely wounded, could have traveled 4.5 miles to Walter Matthews's home and still be in a condition to testify to what happened. Gobo's account was given secondhand at the trial by those who claimed to have heard him speak it. Frank and his companion gave firsthand accounts. The Bedke family also feels that contemporary newspaper reports reflected the sheepmen's side of the story rather than what actually took place. Some believe that Gobo arrived at the Matthews home with $200 on his person31 and ask how a black man at that time could have had that much money when many in the area were struggling for survival. One of the Bedke family has suggested that it could have been blood money paid to Gobo to kill Frank.32 In fact, the Bedkes are proud that their grandfather killed Gobo rather than possibly allowing his own life to be taken. They feel his actions reflected the reality of survival on the frontier. The family points to his acquittal in the second jury trial as ample evidence of his innocence and the rightness of his actions.33

Many questions remain unanswered and are indeed unanswerable. The problem for a modern researcher is being able to look back a hundred years where records of an event are sparse. Much folklore and family tradition exist, but only a few newspaper articles and a secretarial account of the two Bedke trials are currently available. All of the original court records have been misplaced or lost.34 The probate records of Gobo Fango's estate indicate that the medical care rendered to him by the doctor was extensive.35 Yet, despite his injuries, he was able to recount the details of his shooting and draw up a will.

Why was there such a dynamic change between the first trial, in which there was a strong sentiment to convict Bedke, and the second trial just one year later in which the jury acquitted him? Did the emotions of the times, generated by the sheepmen versus the cattlemen conflict, dictate the outcome of the court cases? We know that Gobo Fango was killed and that Frank Bedke did it. The question remains, why? Was it murder or could it have been self-defense?

This frontier episode illustrates the conflicts between segments of society in the west at that period of time. Gobo Fango was a black man in a white world. He was identified with Mormon sheepmen from Utah when they came head to head with strong-willed, non-Mormon cattlemen from the midwest and Texas. This was compounded by a pre-existing animosity between Mormons and non-Mormons in southern Idaho in the 1880s. Regardless of why Frank Bedke pulled the trigger, Gobo Fango was a victim of the times in which he lived.36

H. Dean Garrett

When the first pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, there were several blacks in the group. Later, pioneer blacks came as free people or in some instances as slaves of southern converts to the Latter-day Saint church. Together with others of African descent who came as workers on the railroad, these soon constituted a small black community in nineteenth-century Utah. One of them was Gobo Fango who left South Africa as a child and settled in the Salt Lake valley. He lived in the Tooele, Utah, area and eventually moved to near Oakley, Idaho, where he was killed in 1886. His life is a fascinating, yet sad story—and it remains controversial in Idaho and Utah today.

Edward Hunter, Presiding Bishop of the Latter-day Saints church, purchased a black slave named Gobo Fango sometime after 1865. Fango was fond of his employer, who helped the former slave become an independent sheepherder, and he included the bishop in his will. Fango was murdered by a neighbor in 1886 in a dispute over range rights. Engraving by H. B. Hall and Sons, New York, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved

Gobo Fango was born in the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa about 1855. He was a member of a tribe ruled by Chief Creile. His early life was shaped by the events of the Kaffir wars that raged around him. As a result of the wars and a concurrent famine, his young mother left her tribal home with her three-year-old son and a baby daughter and fled to a nearby farm owned by Henry Talbot.1 Her weakened condition made it impossible for her to complete the journey with both children, so she kept the baby with her and left Gobo in the crotch of a tree out of the reach of wild animals.2 After she arrived at the farm, Henry's boys rescued Gobo. He would soon become an indentured member of the family.3

The Talbots' lives changed dramatically when a friend introduced Henry to the Mormon religion. On December 28, 1857, he was baptized into the church. Six months later his wife Ruth and their children were also baptized; however, no records indicate that Gobo was ever baptized a Mormon. Soon, upon the encouragement of church leaders, the Talbots sold their farm and moved to Port Elizabeth to await the opportunity of traveling to Zion in America. That opportunity came on February 20, 1861, when they boarded the ship Race Horse and set sail for Boston. They had intended to leave Gobo behind with friends, but he complained so much they allowed him to accompany them. The family at that time consisted of Henry and Ruth, their fourteen unmarried children, and their married son Henry James Talbot and his wife and child.4 One account indicates that Gobo was hidden in a blanket and remained undetected until they were at sea.5

Except for a heavy gale in the Caribbean and a collision with another vessel in Boston harbor in which the Race Horse lost its bow, the trip was uneventful. However, the Talbots' arrival in Boston came at an exciting moment in history, for five days earlier shots had been fired at Fort Sumter and the Civil War had begun. President Abraham Lincoln had issued a call for volunteers, and many men were enlisting in the army. Flags were flying, martial music was playing, and great excitement was felt everywhere.

In Boston the Talbot family and Gobo boarded a train, traveling through New York and then on to Chicago. They met their first challenge to Gobo's presence in Chicago where certain people, undoubtedly influenced by the excitement of the war, accused the Talbots of owning a slave. Apparently they set about to give Gobo his freedom. According to one account Gobo, greatly frightened by the uproar, "fled inside the train and one of the ladies of the company hid him beneath her crinolines while the angry emancipationist searched the train without success. To avoid a recurrence of the trouble, Gobo was dressed in girl's clothing and his head was covered with a huge sun bonnet. At awkward times a veil was added to make sure his black face was completely hidden."6 The railroad ended at Joseph, Iowa. The immigrants then traveled to Florence, Nebraska, where they outfitted wagons and undertook their journey west to the Salt Lake valley, joining the company led by Homer Duncan. They arrived in Salt Lake in the fall of 1861 and wintered there. The following spring they moved to Kaysville, Utah, about twenty miles north of Salt Lake, and settled on a farm. Gobo remained with the Talbots and worked on their farm as an indentured slave.

Slavery was at this time still practiced by some Mormons from the south. In 1860 there were twenty-nine reported slaves in Utah.7 There was also a group of free blacks who had joined the Mormon church or who had settled in Utah for employment purposes. Between 1860 and 1870, the black population of Utah grew from 59 to 113. Some of this increase was due to the arrival of the transcontinental railroad.

Gobo was expected to work for the Talbots as a laborer and sheepherder, and life was apparently hard for him. He lived in a shed in back of the Talbots' house. One cold winter his feet froze, and he lost part of the heel on one foot. An acquaintance reported: "When he [Gobo] came to our place, his feet were badly frozen, and he was a cripple until his death. My first recollection was always seeing him wrapping his feet with cloths, and later I remember he had boots."8 She also remembered seeing Gobo take off his boot to show her brother his foot: "The heel was all gone, and he had wool in his boot so his foot would fit better."9 Gobo remained with the Talbot family until he was in his teens.10 Eventually the Talbots either gave or sold Gobo to the Lewis Whitesides family in Kaysville.11

A daughter, Ruth Whitesides Hunter, had a herd of sheep in Grantsville, Utah, and she was finding that her daughters were spending all of their time with the sheep and not learning the domestic sciences. When she remembered that Gobo was with her family in Kaysville, she asked her husband, Edward Hunter,12 if he would obtain Gobo for her. According to Hunter's biographer, "Edward paid for Gobo, then immediately put him on the payroll, just as he did all the hired hands. Gobo regarded Edward as his benefactor and was very fond of him. ..."13

The legal sanction for slavery in Utah ended in the spring of 1862. President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Some slave owners waited to release their slaves until 1865 when involuntary servitude was abolished throughout the United States.14 For instance, it appears that Gobo was sold to the Hunters after 1865.15

The Hunters took Gobo to Grantsville where he helped herd sheep in Utah's western desert through the 1870s. During this time he was able to develop a sheep herd of his own.

A group of Mormon settlers moved from Tooele and Grantsville to Goose Creek Valley, Idaho, as early as 188016 and began to irrigate and farm the land there and to raise sheep. About that same time, Gobo, two of the Hunter brothers, and Walter Matthews went to Goose Creek to run their sheep on the desert. Gobo and Matthews also leased a band of sheep from Thomas Poulton and his sons.17

At that time Cassia County, Idaho, which included Goose Creek, was a "huge expanse of lush range lands and high mountains."18 This area had already attracted the attention of cattlemen from the midwest and Texas who had moved into the area with large herds. The first arrived in 1871, and when sheepmen began moving into the same area, tension between the cattlemen and sheepmen arose. One report complained that "the sheep are getting so thick that they are eating the range out."19 This problem was compounded by the drought that began in the summer of 1885 and continued for several years. "It was dry and hot," a local history states. "Snow did not pile up in the mountains. The grass turned brown, and the cattle and horses cropped it to the ground."20 Due to the combination of overstocking and drought, the range was over-grazed. The cattlemen claimed first rights, the sheepmen disagreed, and a range war developed. Under pressure from the powerful cattlemen, Idaho's territorial legislature passed an act known as the Two-mile Limit which prohibited "sheep grazing within two miles of any possessory claim."21 The range rivalry continued to grow and the cattlemen issued their own edict that all sheepmen must leave.

In this setting early in the winter of 1886, Gobo Fango was herding his sheep in the Goose Creek valley beyond the cattlemen's deadline for leaving. Apparently he was close to the two-mile limit of a claim of Frank Bedke. Early one day Bedke and a companion rode into Gobo's camp and told him to leave immediately. The Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman reported that Gobo challenged Bedke to produce evidence of ownership of the land on which he was herding. Bedke indicated that he did not want to have trouble but wanted rather to be a friend. He dismounted his horse, caught Gobo off guard, and commenced shooting.22 The Deseret News account of the incident indicated that Bedke fired the first shot which "must have been aimed at his temple and carried away his eyebrow." The report continued that Gobo was beaten about the head with the pistol and was then shot again, "the bullet entering at the back part of the head and ranging to the neck, where it stopped close to the jugular vein and not very deep from the skin." A third time Bedke fired, "the bullet entering Gobo's side from the back and coming out near the navel."23 The newspaper indicated that Gobo recovered consciousness and overheard a conversation concerning disposition of Gobo's gun which Bedke had taken. Gobo was eventually able to "crawl about four and a half miles to the Walter Matthews home east of Oakley, holding his intestines with one hand."24 A doctor from Albion was summoned to take care of him, but Gobo survived only four or five days, during which time he made out a will providing for amounts of money to be given to acquaintances and friends, especially to the Hunter family. The rest was bequeathed to the Salt Lake temple fund and the Grantsville City "needy, poor people." Mrs. Solomon E. Hale indicated that "he left me $125 in his will before he died, as also some of my other sisters. He left $50 to one of them. ..."25

Gobo was buried in the Oakley, Idaho, cemetery. Marking his final resting place is a headstone with the simple inscription:

Gobo Fango

died February 10, 1886

30 years old

Frank Bedke and his companion rode to Albion, Idaho, where Bedke reported the shooting to the sheriff. A trial was held, and Bedke pleaded "not guilty due to self-defense." His companion backed his story, and the first trial ended in a hung jury. Bedke was brought to trial again one year later. This time the jury's decision was "not guilty." The events of that trial were reported in the newspaper:

"Frank Bedke, who was tried at Albion a year ago on a charge of killing Gobo Fango, colored, the trial resulting in a 'hung' jury, eleven voting for a conviction and one for an acquittal, has again been tried and acquitted, the first ballot of the jury showing 10 for an acquittal and 2 for conviction. Three ballots only were taken before an agreement to acquit was reached. The dying declaration of Fango was the most serious testimony offered. Judge Waters of Bellerue, Charles Cobb of Albion, and Ransford Smith of Ogden, defended Bedke."26

The man who killed Gobo Fango had traveled the world over as a seaman and then settled in Goose Creek Basin to raise cattle. Frank Carl Bedke was born in Rieth, Prussia, Germany, on November 22, 1844. He had limited schooling in Germany, and at the age of sixteen became a sailor on a ship bound for New York. He did not return to Germany, deciding instead to remain in the States. A family history states, "Near the end of the Civil War Frank Carl boarded a ship in Boston Harbor for San Francisco, sailing around Cape Horn."27 He spent about a year sailing the west coast and then worked on mining claims. In 1868 he traveled to Montana on a prospecting tour and wintered in Bozeman. In 1870 he went to Cottonwood, Utah, and joined the gold hunt, remaining there until 1877. After a short stay in Nevada, he moved to Park City, Utah, and sold milk to the miners. Then in 1878 he traveled to Grouse Creek, Utah, to winter 97 head of cattle. In the spring he took the cattle to Goose Creek Basin, Idaho, to a place now called Bedke Spring. He lived in a dugout and rode range for other operations until he was able to fully establish his own.

When he arrived in the Oakley area, it was about the same time the Mormons from Grantsville, Utah, appeared there. A close-knit group, the Mormons were not particularly open to outsiders. Bedke felt that he was an outsider, but he was intent on staying in the area. When an Indian uprising occurred, he remained and co-existed with the Indians while most of the other settlers fled to Kenton, Utah, for safety.

He married Polly Ann McIntosh on January 2, 1882.28 Polly Ann was born in Grantsville, Utah, in March 1863 to Solomon P. and Mary Harper McIntosh. At the age of seventeen, she drove a team and wagon from Grantsville to Idaho. Her marriage to Bedke was not viewed favorably by her family or the Mormon church, and this eventually led to her estrangement from both.

During the early years of their marriage, the Bedkes and their Mormon neighbors found themselves in conflict. One cause was the fact that Polly's husband was not Mormon. A second was the strong anti-Mormon feeling among other settlers in southern Idaho at that time. A third and perhaps more important source of conflict between the Bedkes and their neighbors was the dispute between the cattlemen and the sheepmen. The natural animosity between these two groups was amplified during the drought.

Despite these early difficulties, following his acquittal in the second jury trial Bedke became a successful and respected member of his community. One biographical volume stated that he was "active and forceful in the affairs of the community and aided in promoting its welfare both as a private citizen and as a useful public official, serving faithfully as a school trustee for nine years [and was] a firm and zealous working Democrat in political faith, giving loyal and serviceable support to the candidates and policies of his party."29 During the latter part of his life, he was described as a man "well prepared to meet all emergencies and perform every duty of citizenship with readiness and ability. He [was] a valuable element in the progress and development of Cassia County, giving substantial and helpful aid to every commendable undertaking for its improvement and the comfort and convenience of its people. Among the enterprising and public-spirited citizens of the county, he is in the front rank, and is secure in the esteem of all classes of the people."30

The death of Gobo Fango has inspired a voluminous amount of folklore and conflicting stories. The nature of the homicide is disputed by the descendants of Frank Bedke who feel that their grandfather was justified in killing Gobo Fango. This is based on several factors. They view Frank as an independent, self-sufficient man who reacted to any challenge to his rights or livelihood. In the eyes of his family, his reaction to the sheepmen, and especially Gobo, was right and justified because, according to their claims, Gobo was within the two-mile limit and refused to respect the lawful owner of the land. Second, the Bedke family finds it hard to believe that Gobo, so severely wounded, could have traveled 4.5 miles to Walter Matthews's home and still be in a condition to testify to what happened. Gobo's account was given secondhand at the trial by those who claimed to have heard him speak it. Frank and his companion gave firsthand accounts. The Bedke family also feels that contemporary newspaper reports reflected the sheepmen's side of the story rather than what actually took place. Some believe that Gobo arrived at the Matthews home with $200 on his person31 and ask how a black man at that time could have had that much money when many in the area were struggling for survival. One of the Bedke family has suggested that it could have been blood money paid to Gobo to kill Frank.32 In fact, the Bedkes are proud that their grandfather killed Gobo rather than possibly allowing his own life to be taken. They feel his actions reflected the reality of survival on the frontier. The family points to his acquittal in the second jury trial as ample evidence of his innocence and the rightness of his actions.33

Many questions remain unanswered and are indeed unanswerable. The problem for a modern researcher is being able to look back a hundred years where records of an event are sparse. Much folklore and family tradition exist, but only a few newspaper articles and a secretarial account of the two Bedke trials are currently available. All of the original court records have been misplaced or lost.34 The probate records of Gobo Fango's estate indicate that the medical care rendered to him by the doctor was extensive.35 Yet, despite his injuries, he was able to recount the details of his shooting and draw up a will.

Why was there such a dynamic change between the first trial, in which there was a strong sentiment to convict Bedke, and the second trial just one year later in which the jury acquitted him? Did the emotions of the times, generated by the sheepmen versus the cattlemen conflict, dictate the outcome of the court cases? We know that Gobo Fango was killed and that Frank Bedke did it. The question remains, why? Was it murder or could it have been self-defense?

This frontier episode illustrates the conflicts between segments of society in the west at that period of time. Gobo Fango was a black man in a white world. He was identified with Mormon sheepmen from Utah when they came head to head with strong-willed, non-Mormon cattlemen from the midwest and Texas. This was compounded by a pre-existing animosity between Mormons and non-Mormons in southern Idaho in the 1880s. Regardless of why Frank Bedke pulled the trigger, Gobo Fango was a victim of the times in which he lived.36

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement